Amplified Architecture & TodaysArt Agency

Festival documentations

R&D

Amplified architecture

TodaysArt is a cultural production agency, specialized in creating groundbreaking experiences that unite art and technology. Over the past 15 years, TodaysArt has been a catalyst for innovation and creativity, presenting the best in contemporary audio-visual and immersive art. Based in The Hague, The Netherlands, TodaysArt’s activities comprise an annual festival, an artist-lab and a number of creative projects.

Since 2002, TodaysArt has built up an impressive profile, commissioning productions that set new benchmarks in the fields of audio-visual and immersive art, through direct relationships with today’s leading artists and creative technologists.

TodaysArt is committed to progressing cultural innovation. As a member of four Creative Europe projects, and with partnerships in Europe and Asia, TodaysArt is consistently involved in international projects, bringing pioneering talent to local audiences across the world.

Creative Europe Projects:

We are Europe

SHAPE

BlockchainMyArt

Beyond Quantum Music

Festival documentations

2019: Consciousness edition

2018 edition

2017 edition

2016: Public under construction edition

2015: Festival on sea edition

2014: Sea of random data edition

2013: Unauthorised permission edition

2012: Imagination Reality edition

Festival editions’ catalogues and programs on ISSUU

Online platform

- Social networking strategies and campaigns

- CRM Contacts and documents management tools

- Editorial, internal publishing workflow

- Architecture and structure/ Roles and responsibilities within organisation and network

- Archiving concept

Initiating TodaysArt Brussels

By joining Cimatics festival, Brussels, Belgium into TodaysArt Platform. Shared communication tools, web development, strategies and tactics.

Expanding brand internationally.

TodaysArt Russian and Japanese editions.

Amplified architecture

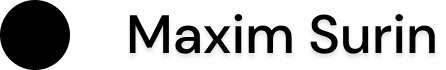

Amplified Architecture is TodaysArt’s hybrid festival module which is used as a presentation platform for reflections on architecture and urban infrastructure.

Short introductions to festival´s editions:

AA temporarily transforms the surroundings by amplifying or ignoring the adjoining architecture and consists of monumental projects, site specific works, media facades, interventions, installations and performances often commissioned and co-produced with the artists.

Love the Real City 2010

‘Love the Real City’ implies that there is a city that is not real. The ‘unreal’ city could be the abstract, administrative view of the city or the Cultural Capital 2018 bid of The Hague. City developments that have more ambition than facilitate functions. A creating process that doesn’t take existing social-cultural structures into account. So what is the real city? Experiences, participation, engagement, daily routines, a festival like TodaysArt?

At the logistic heart of TodaysArt 2010 is the Spuiplein. Here, at the centre of The Hague, the programme is focused on art in public space and the city experience with the Amplified Achitecture programme, surrounded by high expectation and established façades.

This year, together with many other cultural organisations, TodaysArt highlighted the waste and misuse of cultural places through one of the last legal squat actions in the Netherlands at the Asta theatre. By infiltrating a city space in this way, and through this year’s festival, we hope to have an impact on the cultural understanding of the city at all levels.

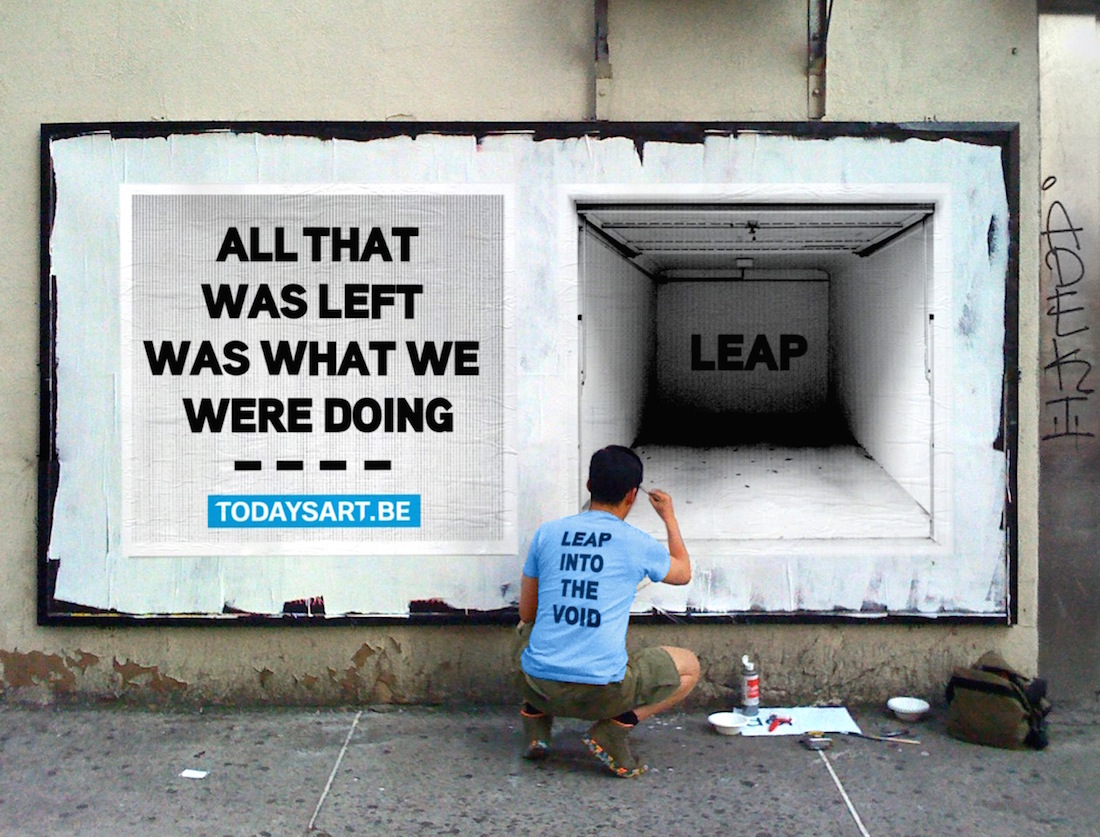

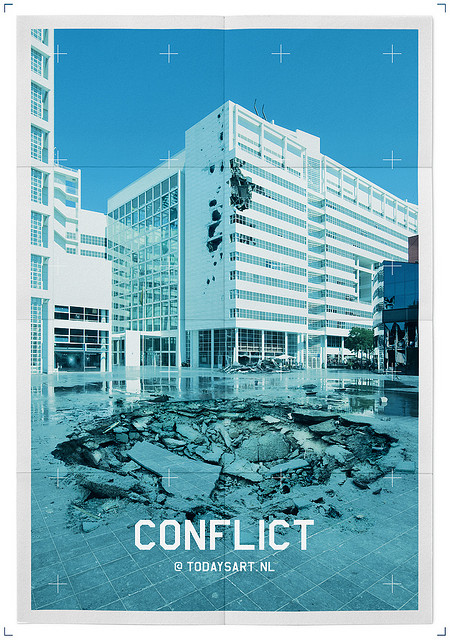

City of Conflict 2009

Everyday we consume numerous texts and images that represent ongoing conflicts and disputes. Although not too consciously, most of us are completely accustomed to the rhetorical vocabulary that is often used. What do these textual and visual messages actually tell us? Do they give us an objective insight or do they merely tell us something about the representation of conflict in general?

The problem is rooted in the actual consumption of these messages. The independence of a western recipient is always questionable. In one way or another we are influenced by our roots. And so it is that for the Western world, most representations of western power have a trustworthy connotation. One might not support certain political or social convictions, but the basic vocabulary that represents Western power is common ground. Consciously or subconsciously we simply know how to interpret most signs and symbols. We only ask questions about sincerity when unconventional components enter these preconceived messages.

Simple common sense or generalisations take over; leaders become despots, the good cause turns into a questionable form of corruption and the message is interpreted as propaganda. This is even more imminent when we are confronted with representations of non-Western power. Every exotic adjective or unconventional variation colours our perception. A portrait that is a bit too polished is taken as an indication for a totalitarian regime and a display of power that is a little bit too obnoxious for our taste is interpreted as a sign of an unstable situation. What is the actual situation and what other messages do we contract from our cultural perspective? The known and unknown in any given situation define how we interpret most representations of conflict.

The same goes for the images and texts that directly represent aggression, violence and despair. Graphic depictions of conflicts are hard to ignore. But do we truly understand them? Most Western societies do not know what actual violence means. Our closest reference might be an argument, an accident or an exceptional eruption of aggression. The impact of real destruction, actual life-threatening situations and the unbearable insecurity that goes with it cannot be understood in a metaphorical representation.

However, we cannot deny the compulsive thrill we sometimes experience when a violent message is consumed. The entertainment industry has been exploiting this feeling for years. With the introduction of modern communication tools this compulsive urge has found a new platform. The representation of conflict is democratised by popular demand. Within this context a journalist or press-agency no longer defines what the image of a conflict is. Everyone reports and not a single graphic detail is left out. Yes, you might get a better insight, but inaccuracy and hype become more important. Eventually only the in-comprehensive thrills remain.

TodaysArt has invited the theme ‘conflict’ to the city of peace and justice. Again one could ask him or herself what these adjectives actually stand for. One wonders why The Hague is actively marketing itself this way. For the average Western person, the fact that the city claims this part of conflict for itself is probably a positive thing and interpreted as The Hague wanting to promote peace and justice. Others might interpret it as simply a matter of marketing. “Peace and Justice” is the marketing equivalent of “Conflict” and the message it sends out has a Western connotation and morality. One could feel that it is dubious for a city to claim the name ‘city of peace and justice’ instead of having others claim it for them. Again, the vocabulary can be lost in translation. There is no right or wrong. Only the obnoxious game of interpretation truly says something about the identity of conflict.

Blue Light District 2008

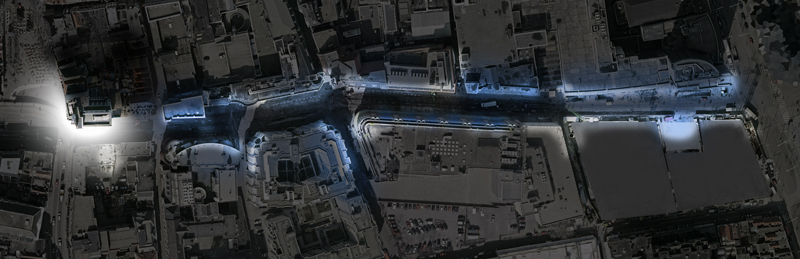

Location: Volharding/Grote Marktstraat, The Hague

Concept, Design & Programming: LUST

Giant lights that light up the buildings in the Grote Marktstraat, one of the main streets in the city center of The Hague. The buildings are used as pixels, creating an enormous effect of depth in the street. Controlled by a simple Processing script and allowing for interaction with passers by.

THX: The Hague International Airport 2007

Concept

Turning the city of The Hague into an International Airport.

The Grote Markstraat – 600 meters long – was transformed into a landing strip, using 36×6 indivual controllable lights and 48 2000-Watt speakers, creating the experience of airplanes landing in the street. The landing strip connected the two main areas of the festival, with a total of more than 25 stages throughout the city. The Volharding building functioned as an arrivals and departures sign, all tied together by audio-announcements of ‘incoming’ artists in eight different languages.