Classified subjects

Photography, Photographs and Public Libraries

By Pete James from The Source Photographic Review

In recent times a growing body of work has begun to chart and re-assess the historical relationship between the photograph and institutions of knowledge: i.e. museums, libraries and archives. In some situations this work has resulted in the restructuring of the systems of classification, the physical relocation of collections and the development of new roles for the photograph within these domains. Writers and curators have also sought to develop new understandings of the history of books illustrated with original photographic prints and that of the history of the literature of photography.

Together this work has helped to establish new understandings of the institutional, material and cultural history of photography: a history that goes beyond the simple canonical model of great pioneers and artists. This essay seeks to open up debates about a related, yet relatively unexplored field: that of public reference libraries and the resources they dedicate to representing photography, this being primarily expressed through issues such as the books that are purchased and the way they are catalogued and physically ordered within the institution. This is in itself a substantial subject area and one that cannot be fully understood in isolation from the related history of libraries and of photography.

However, within the constraints of this essay it is not possible to do more than present some of the key questions relating to this subject. These questions will be addressed largely in reference to my own institution, Birmingham Central Library: one of the largest public reference libraries in Europe and home to one of the national collections of photography.

The most common definition of a library is ‘a building or room containing a collection of books’. However, libraries come in all different shapes, sizes and specializations i.e. private or subscription libraries; national libraries; public libraries (lending and reference); academic libraries; art libraries; museum libraries and those of learned societies. Each serves a particular function and often a specific constituency of users. Public reference libraries were first established in Britain after the passing of the Public Libraries Act by Parliament in 1850.

They were created to provide all classes of society with free access to books, journals and newspapers and were part of the same reform movement that sought to establish public museums and art galleries to enable the so-called ‘elevation of the masses’. In many cases the intimate connection between the two was such that one was constructed or given space within the other. Most of the large metropolitan public libraries that exist today provide both reference and lending services. In so doing they strive to uphold the founding principle of free public access to their resources and issue ‘customer service statements’ which seek to explain not so much what they are as what they exist to do. My own institution for example ‘exists to provide promote and encourage access to reading, information, lifelong learning, leisure and cultural activities for everyone’.

Public reference libraries and photography developed at a comparable historical moment during the first half of the nineteenth century. Indeed photography, public libraries, museums and art galleries were all part of a conjoined positivist enterprise: to collect, collate and disseminate knowledge about the world so as to facilitate social progress. The figurative powers of photography and belief in its fidelity to nature led to its widespread use as a tool to aid the study of history, science, art, industry, topography and nature – both in terms of collecting and disseminating information.

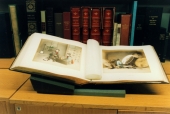

Photographs stored in albums and portfolios were thus placed into an already established system of storage and cataloguing developed for books, prints and drawings within the library. The potential for mass reproduction made possible by Talbot’s negative/positive process also led to the widespread use of laid down photographs as illustrations in books and these were acquired in large numbers by libraries of all kinds after the introduction of the albumen print in 1851. These were also placed on the library’s shelves in accordance with the existing systems of classification.

In addition to becoming an aid to learning, photography itself naturally became a subject of study. The desire for knowledge about the processes and equipment needed to make photographs was largely met through the production of technical literature and within three years of the announcement of Daguerre and Talbot’s processes in 1839, no less than thirty-two technical manuals were published. Photography’s rapid development led to the publication of more comprehensive works such as photographic dictionaries, encyclopaedias and historical accounts of the process and its various applications. Periodicals solely devoted to photography were not far behind, one of the earliest English publications being The Liverpool Photographic Journal, the forbear of The British Journal of Photography, first issued in 1854.

From these early beginnings the rapid growth in the publication of photographic literature can perhaps best be gauged by comparing the entries in two bibliographies of photography published over a century apart. William Jerome Harrison’s bibliography published in The Photographic News in 1886 contains some 340 entries. Laurent Roosens and Luc Salu’s bibliography published in 1989 contains some 11,000 entries in more than a dozen languages arranged under some 3,000 subject headings and subheadings.

However, it is not simply the sheer number of publications that increased during this period, but also the type of publication. Perhaps the most significant development in this regard was the introduction of the half-tone process in the 1880s. Although the albumen print and photomechanical processes such as the Woodburytype made possible the production of a significant range of photographically illustrated books, it was the introduction of the half tone process – which enabled the transfer of the photographic image to the printing block – in the mid 1880s that truly revolutionised both the scope and scale for the publishing of books on photography and those illustrated with photographs.

Within the specific realm of photographic literature it enabled publishers to navigate a shift away from the format of earlier publications comprised solely of text and those illustrated with ‘engravings’ made after original photographs or photomechanical reproductions. It made possible the production of new forms of illustrated photographic literature ranging from general and thematic histories of photography to monographs by and about individual practitioners.

Librarians seeking to collect, organise and make accessible the ever expanding variety of publications about photography and photographically illustrated books have always faced two key problems: firstly, the manner in which the process is considered simultaneously both an art and a science; and secondly, the plurality of discourses in which photography had participated. In order to help them position books in the right place on the shelves so as to make them easier for us/them to find, librarians most commonly use the Dewey Decimal System (DDS) which associates a number sequence with every field of knowledge. Within the DDS knowledge is divided into 10 fields and amongst these ten main classes The Arts are associated with the numbers in the 700s sequence.

Each main class has ten sub-divisions and within this sequence Photography & Photographs are categorised in the 770s sequence. Further sub-divisions provide further numerical categories, for example: techniques, procedures, apparatus, and equipment (771); specific fields and special kinds of photography and related activities (778) and finally photographs (779). The current edition of the DDS (20/21) contains no less than eight pages devoted to the fields for classifying photography. As the term ‘current edition’ implies, the DDS is subject to periodic revision and items appearing in one class in one edition may subsequently be assigned to another in a later version. Just to complicate matters further, subjects such as photogrammertry and photomechanical reproduction can also be classified in sequences outside the 770s assigned for photography.

In seeking to place any given publication within this or other sequences within the DDS, the first question a librarian usually asks when confronted with a new book of photographs is: is the focus of the work on the artistic value or technical aspects of photography? In other words, does the work truly belong in the category of science or arts? If yes, the work belongs in the 700s sequence; if no – if the focus of the work for example is on the plight of the poor rather than the artistic qualities of the photographs or the equipment or processes associated with making the images – then the work is classed with the subject of the photographs. The DDS is of course subject to the interpretation of individual librarians, these interpretations change over time and anomalies occur as a natural part of this process. For example, Birmingham Library holds a copy of a 12-volume work British Museum Collections (1872) illustrated with over 900 original photographs. Each volume deals with the antiquities held in different departments, i.e Egyptian, Assyrian, Greek, Etruscan and British, etc.

The strict application of the DDS means that the work is currently split between two subject information departments, Local Studies and History (3 volumes) and Arts, Language and Literature (9 volumes) with three different DDS class marks being used to classify the volumes. Elsewhere Fay Godwin’s book Landmarks (1998) is classified under ‘environmental photography’ in the Science and Technology Department field of applied photography, and is found alongside books dealing with cameras, process and optics. Another work by the same artist,Remains of Elmet, A Pennine Sequence, with Poems by Ted Hughes (1979) is catalogued and held by The Arts, Language and Literature Department.

Whilst this in itself may appear problematic, it is possibly made all the more so in Birmingham because books on photography are split between two subject information departments and these are located on separate floors of the building. However, it was not always so. Birmingham Library was originally broadly divided into two main areas: Humanities and Science and Technology. Within this structure books on photography were largely found in the Science and Technology section. In the 1970s a vogue for a broader range of subject information departments evolved within library practise. The adoption of these new structures in Birmingham saw the formation of a new Arts, Language and Literature Department, and within this new domain material from various parts of the library were drawn together into a subject area that dealt with photography as an art form within the context of the fine arts.

These changes in themselves reflected a general growth in interest in photography for the 1970s was a period when photography became part of the world of museums, higher education, the art market and culture in general. This was marked at a national level by the Arts Council of Great Britain’s formation of a Photography Committee (1971) and landmark exhibitions such as the Bill Brandt show at the Hayward Gallery (1969) and From Today Painting is Dead, shown at the V&A in 1972. These in turn prompted the appearance of numerous new books, exhibition catalogues and journals which sought to re-evaluate and re-place photography within the realms of the fine arts.

At the time of writing it was not possible to establish the extent to which the organisation of photography books and subject information departments in Birmingham Library exists in other institutions in the UK. However, there are undoubtedly other models of practice such as that adopted at Finsbury Library. Here books and journals on all aspects of the subject were drawn together to form the Metropolitan Special Collection on Photography, the largest such collection in the South East. The collection is housed in a closed access store and access is generally made by appointment. The organisation of books and journals in this fashion raises yet another question: at what point does a library stop being a library and become a museum of books and journals?

This issue was taken up by Douglas Crimp in his 1993 essay ‘The Museum’s Old, the Library’s New Subject’. Crimp describes how in the 1970s, Julia van Haften, a librarian in the Art and Architecture Division of the New York Public Library (NYPL) became interested in photography. In pursuit of this interest she discovered that ‘the library itself owned many books containing vintage photographic prints’ dispersed throughout its numerous thematic collections. She decided to organise an exhibition of this material and in the process of doing so realised for the first time that the library ‘owned an extraordinarily large and valuable collection of photographs… because no-one had previously inventoried these materials under the single category of photography.’

At the time she installed her exhibition ‘photography’s prices were beginning to sky-rocket’ and books that previously were not deemed worthy of a place within the library’s Rare Books Division were now worth a small fortune. Van Haften went on to create a new library division, that of Arts, Prints and Photographs to which she added photographs culled from all the other library departments. In so doing, the materials were ‘reclassified according to their newly found value, the value that is now attached to the “artist” who made the photographs’. Crimp states that ‘thus what was once housed in the Jewish Division under the classification “Jerusalem” will eventually be found in Arts, Prints and Photographs under the classification “Auguste Salzmann”.’ He goes on to conclude that ‘if photography was invented in 1839, it was only discovered in the 1960s and 1970s’.

Crimp’s critical assessment of events in NYPL addresses understandable concerns about the typological re-classification and re-organisation of such materials. Furthermore, the issues he raises relating to books illustrated with original photographic prints are now equally applicable to the domain of early photographic literature, much of which could be assigned rare books status. Perhaps librarians have concerns that Crimp has not considered? For example, the free public access provided to rare and valuable volumes such as those he describes have always presented problems of theft and mutilation. The conflict between free public access, conservation and security are not easy to resolve, particularly within the limited resources available to most libraries.

The advent of digital imaging and computer catalogues undoubtedly provides one solution by allowing the creation of digital surrogates so that a volume or image can exist and function in two realms within the same institution simultaneously. This is the approach currently being adopted by The British Library where specialists are compiling a database (currently standing at some 5,000 entries) of works containing original photographs and texts relating to the development of photography and the early processes of the photo-mechanical production of books.

The example of the mis-classification (?) of Godwin’s book cited earlier is perhaps symptomatic of another set of problems linked to the changing status of photographs and photography since the 1970s. In the early part of that decade photographers like Paul Hill began making work that addressed debates about photography as an autonomous means of self-expression. Whilst Hill and his contemporaries drew upon nature for their subject matter, they were creating images, sequences and photo essays that sought to go beyond the forms of documentary practise that dominated photography in the 1960s and make work that operated on the level of metaphors: photography as art. In his 1993 essay, Crimp gives an example of how one photographic book presented problems for the librarian at NYPL.

He recalled that when hired to do picture research about the history of transportation he found himself browsing through their stacks where he came across a copy of the book Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1963) by Ed Ruscha. Crimp recalled thinking ‘how funny it was that the book had been mis-catalogued and placed alongside books about automobiles’, because he knew ‘as evidently the librarians did not, that Ruscha’s book was a work of art and therefore belonged in the art division.’ Crimp subsequently changed his mind and concluded that Ruscha book made ‘no sense in relation to the categories of art according to which books are catalogued in the library’. For him, the fact that there was nowhere for this work ‘within the present system of classification’ was ‘an index of the books radicalism with respect to established modes of thought’. Unfortunately Crimp’s interesting observation gives little comfort to the poor librarian seeking to place such works within the existing systems of classification. The more recent advent of ‘artists using photography’ perhaps serves to complicate the matter even further. One only has to think of the manner in which many commentators (mis)located Richard Billingham’s work Ray’s A Laugh (1996) within the realm of documentary practise to understand the potential problems for the librarian or cataloguer.

Problems relating to the question of ‘who’ and therefore ‘how’ such books are selected and catalogued are one of many points raised by Amanda Duffy in her essay ‘Visual Arts Provision in Public Libraries: Threats and Opportunities (Arts Libraries Journal 1999)’. Duffy suggests that the loss of knowledge and expertise caused by cuts in the number of specialist arts posts in public libraries, the replacement of these posts with ‘the so-called generic librarian’ and increased reliance ‘on non-professional staff to answer enquiries and, in some cases, to select stock’, may cause problems in the future. Given the range and number of publications on photography now produced every year, an interest in the subject seems a minimum requirement for anyone asked to select stock from the publishers lists supplied to public libraries by the likes of Photoworks and Dewi Lewis Publishing.

Another key factor in the decision making process is that of resources – for resources read dwindling library budgets. In a world of limited resources the increasing costs of some photography publications – as opposed to those of popular fiction titles, travel books or children’s literature, etc – can lead to questions of priorities. Why buy one expensive monograph when the same amount of money can buy three, possibly four other titles?

The matter of free public access and censorship has also proved a re-current problem for librarians in relation to some photographic literature. Loudly voiced concerns about the acquisition with public funds of photography books dealing with the body, sex and gay and lesbian photography, volumes deemed ‘pornographic’ by some, have raised many issues. Librarians have faced similar issues with other forms of art books – particularly those dealing with human anatomy, the nude and erotic imagery.

However, it could be argued that the increasingly graphic nature of the imagery in some more recent books and the widespread controversy caused by their publication has brought greater public and professional attention to this matter. In the past librarians adopted a variety of strategies for dealing with such issues. These included housing such works in a special locked bookcase in the chief librarian’s office, and issuing this stock under the strict public scrutiny of a member of staff on the so-called ‘desks of shame’. For many years in Birmingham, books such as Henry Mortenson’s technical manual Lighting the Nude(1950), in which all the illustrations were subject to the tasteful touch of the air brush, were served under such conditions.

More recently the public controversy surrounding books such as Sally Mann’s Immediate Family (1991), which included images of her children naked, and Madonna’s steel bound volume Sex (1992), with photographs by Stephen Meisel of the singer and other models acting out sexual fantasies, undoubtedly caused many librarians to consider whether they should acquire and place such items on their shelves. Perhaps the most influential case was the raid carried out by members of the West Midlands Paedophile and Pornography Squad in the The Library of the University of Central England in 1998.

The police confiscated a copy of the book Mapplethorpe (1992), declared parts of the book obscene, and placed the University’s Vice Chancellor under threat of imprisonment unless he agreed to the destruction of portions of the book. This led to the withdrawal of all Mapplethorpe titles in many public libraries until the case was finally resolved.

Many issues relating to reference libraries and the resources they dedicate to representing photography remain to be identified and addressed. For example, do librarians place books on digital photography, the software associated with image management and desktop publishing with photography or computing? That, perhaps, is the subject for another essay altogether.

I would like to thank my colleagues Patrick Clarke and Norman King for their help in researching this article.